There are a few questions I'm frequently asked, either in interviews or when I meet readers at comic conventions and so on: "What made you want to write comics?" (or the companion question, "What was the first comic that got you hooked?") and "Where do you get your ideas?"

In general, most writers hate to answer that "ideas" question, because the graven-in-stone truth is: WE. DON'T. KNOW.

In my case, I think it all comes back to the first question, and my answer to it.

When I was in grade school, my family and I went on a vacation. I grew up on the East Coast, and it was fairly typical to pack the family off to, say, Florida (with the requisite stops at Disney or Busch Gardens). My family never did that. We rarely took family trips at all, save to visit family; we certainly never went to the Grand Canyon or Yellowstone.

My parents worked very hard, and for them, a vacation meant ignoring the phone, staying quietly at home and doing the things they loved to do, rather than the things required to put food on the table.

Mom needlepoints, works in stained glass, reads voraciously.

My father is a serial collector of hobbies; he's a skilled and talented magician (who still, in his professional role as a pharmacist, puts on "poison prevention programs" for pre-schoolers, in the form of a magic show); he plays guitar with enthusiasm and no small ability; he builds plastic model kits (his preference, World War II German armor in 1:72nd scale), researching them down to the smallest rivet and modifying stock kits to repair the errors in them.

(An aside: I have many fond memories watching my Dad working at his modeling bench; in one diorama of street fighting in what I presume is Berlin, he had cut 1:72nd scale brick rubble out of modeling clay, by hand.

My personal favorite of his projects is a diorama of a bored-looking Wehrmacht trooper, standing next to a parked tank, standing guard. Behind him was a stack of oil drums, and a small wooden sign. The sign -- handmade, in scale -- was lettered, also by hand, to read "No Smoking" in German. And, so small it is best viewed with a magnifying glass, a tiny cigarette in the guard's hand, the end slightly blackened. That, to me, is my Dad in a nutshell: sly and clever.)

So, it was rather odd when my family decided to have a "normal" vacation. Naturally, they chose a venue more "them," though: Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia. A working Colonial village -- candlemaking, chamber music, and so on.

I was eight or nine years old, if memory serves, and for me Colonial Williamsburg was akin to watching paint dry. For days. I could not possibly have been more bored.

The trip to and from Virginia, however, was an adventure. It was the first time I ever traveled via train. I even had my own compartment, located at the opposite end of the train from my parents. I remember a tremendous sense of intrigue, and freedom, and excitement. It was like being James Bond.

We had a brief layover each way, stopping off for several hours in Washington, D.C., so we hastily visited the Smithsonian; whereas Williamsburg had been excruciating in its boredom, the trip to the Smithsonian was the highlight of the vacation—I went from James Bond to Indiana Jones, spelunking through vast cities of ancient treasure.

Unfortunately, we only had a brief window of opportunity, so it was impossible to see much, but I remember loving the Air and Space Museum—gazing in awe at the Spirit of St. Louis, touching the moon rock, obsessing over the model of the USS Enterprise.

I was less enamored of the Natural History Museum (though I recall one room that was a giant honeycomb/bee hive. There was a monster-movie thrill there, being inside the buzzing hive).

On the return trip, my parents allowed me to choose some items from the gift shop. Time was getting short, and I had to choose from all manner of glittering loot. I ended up selecting a pen-sized telescope/microscope device (from which, back in James Bond mode on the train, I engaged in "surveillance"), some freeze-dried astronaut ice cream (awful, genuinely awful) and a book.

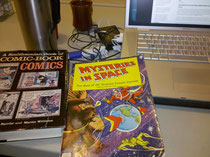

The book was The Smithsonian Book of Comic Book Comics, and it was probably the most important book I've ever bought, in terms of impact on me.

It is a lovely volume, filled with reprints of very old comics, selected -- with impeccable taste -- by the editors (Michael Barrier and Martin Williams).

These weren't just reprints; they were photographically reproduced from the original stories; you could see the texture of the original newsprint, the paper yellowing from age.

It was wonderful, eye-opening stuff. I already liked comics (my father turned me on to his favorites: Batman, Green Lantern and Uncle Scrooge, despite my mother's disdain for the medium) but the material in this volume was light years beyond anything I'd ever seen.

Some of the obvious material was there: reprints of the first appearances of Batman and Superman, some Captain Marvel, some Plastic Man. I gravitated to the superhero stories, for sure, but I found the Little Lulu and Donald Duck (Carl Barks, of course) selections entertaining, as well.

Other stories were complete revelations: Basil Wolverton and George Carlson stories of incredible charm and whimsy; several Pogo Possum stories (which no doubt predisposed me to affection for Jeff Smith's much-later Bone tales). Sheldon Mayer's "Scribbley" was one of my favorites, blending fever-pitch slapstick with an almost autobiographical style. The book was also my first exposure to both Will Eisner and The Spirit as well as Harvey Kurtzman, and E.C. war comics.

More importantly, each section featured a brief history of the character or story, and the creators involved. I devoured those essays (which also contained my first exposure to Harlan Ellison, a writer who's work remains at the top of my reading pile; the editors wisely mentioned and excerpted his appreciation of George Carlson, which I later tracked down in my quest to complete my Ellison library).

I had always enjoyed comics, but for the first time, I realized actual people spent time and energy making the stories, just like I spent time and energy drawing and writing stories for myself.

It was a thunderbolt moment: Making stories can be someone's job.

Followed by another, even more subversive realization: If I work at it, making stories can be my job.

(What followed was a decade or more of being yelled at for reading books that weren't assigned, not doing my homework because I'd been figuring out how best to draw a particular scene, "not working to potential" and various other parental headaches.)

A year or so later, as a birthday present, I received a copy of a Fireside book of reprints of DC science-fiction comics from the 1950s, Mysteries in Space. Edited by Michael Uslan, the book was broken down into various chapters (each containing anywhere from one to seven stories, culled from Strange Adventures,Mystery in Space, and even Justice League of America and Detective Comics). Chapters ranged from "Aliens Visit Earth Today" to "Space Heroes of the Future."

The book reprinted several Frank Frazetta, Carmine Infantino, and Murphy Anderson stories -- among dozens of other luminaries. Space Ranger, Adam Strange, The Martian Manhunter, Captain Comet, The Atomic Knights, Space Cabbie, Star Hawkins, Tommy Tomorrow and the Planeteers, the Museum of Space—concepts that burned themselves into my already-dizzied-by-Star-Warsbrain, and still burn brightly in my mind today.

(Lest you think that's hyperbole, let me assure you that I've never forgotten those pages; Reprinted in black and white in the introduction is a Mystery In Spacecover, featuring Ultra, The Multi-Alien, a character I'd dearly love to write today...and almost managed to, in Checkmate #17, in a scene that had to be cut.)

Between The Smithsonian Book of Comics Book Comics and Mysteries in Spacewas the skeletal structure and nervous system of American superhero comics.

That's the long answer to the "What made you want to write comics?" question. I wanted to add my name to the roster of people who made that particular kind of magic.

But there's a bit more to it.

The summer before I entered 8th grade, I was living with my grandparents. (My family was in the process of moving, and building a house, and the contractors had failed to meet deadlines. It was decided, rather than make me switch schools mid-year, I should live with my grandparents.)

It was a pleasant enough summer; I didn't know very many people, and I kept to myself, so I read a lot, a habit that persists to this day.

An employee at my father's drugstore happened by one evening, with two large boxes in the back of his pickup truck, a box for a full-size refrigerator and the container for a washing machine.

He pulled into the driveway, waved me over, and I helped him wrestle these bulky, ridiculously heavy boxes out of his truck and into my grandparents' garage.

He opened the first box and pointed inside. "Your dad says you like comic books. I've had these in my barn for a while and thought you might like to read them."

Inside the boxes were hundreds of old comics, the most recent perhaps from the late 1970s. They'd had their covers stripped; unsold books from the newstand at the drugstore, which should have been destroyed, but were instead tossed in a box and socked away for years.

The books were in awful condition, but they were all readable, and I spent that summer devouring every comic in those boxes.

There was lots of superhero material (including Charlton characters, but also the Dell heroes like Doctor Solar, Turok and Magnus, Robot Fighter), but there were also romance comics, westerns, war comics, funny animal comics, crime comics and more. And I read them all, cover to cover. Every page of story, every ad, every letter in every letter column.

If The Smithsonian Book of Comic Book Comics and Mysteries in Space were the skeletal structure, then these boxes were the map to the genome of American comics.

----

When it comes to "where I get my ideas," I tend to remember those boxes of old, battered comic books. Every time I sit down at the keyboard, I'm chasing that feeling of wonder that I experienced when I dove inside and wrestled out some forgotten, flawed gem of storytelling. Every page of gaudy costumed adventure, every moment of terror in the foxholes, or swooning romance were pretty heavily imprinted on me that summer, and ultimately, a lot of what I write is to satisfy that hunger for the "next, spine-tingling chapter!"

There's more to it than that; I tend to try and fill my head with "stuff"--I read voraciously, mostly current events and non-fiction, and eventually, with all that information sloshing around in my backbrain, eventually the dots start to connect. A half-remembered phrase from a news story on NPR connects with a passage from a recently-read copy of a non-fiction book and sparks other connections, other points of intersection between the information I've absorbed over the years.

Enough of those points of intersection occur, and suddenly an "idea" pops out. (That's about the best way to describe it; the process is rarely gradual for me. Normally it happens suddenly and brutally, like a sneeze or hiccup.)

I don't have a particularly good explanation for that alchemy; I visualize it as a bunch of pieces of popcorn flying around inside an air popper. Eventually, the velocity and angle fires the popped kernel into the bowl. Boom: there's an idea.

And from that point, the real work begins: taking that idea, running through the various permutations in which that idea can be spun into actual story, and then staring at the blank page until you find the point where you can fall inside it.

And then comes the struggle to make the magic happen again.

Write a comment

JJ (Wednesday, 13 January 2010 14:20)

Very interesting and informative.

Thanks for sharing.

Russ (Wednesday, 21 April 2010 12:35)

That was awesome. I have followed The Shield religiously and have thoroughly enjoyed it. I'm looking forward to the Mighty Crusaders. You tell some great stories man. Keep up the good work.

Eric Trautmann (Wednesday, 21 April 2010 13:36)

Thanks, Russ! Glad you're liking the work. I'm certainly having a blast.

Best,

-E